The Labor Market Cracks - What's Next?

This post is a full version of the EPB Weekly Economic Briefing #31

This post is a full (free) version of the EPB Weekly Economic Briefing #31.

If you find this report helpful, please subscribe and share this with friends and colleagues who you think would find it valuable.

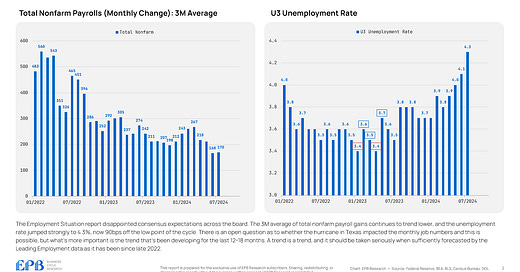

The Employment Situation report disappointed consensus expectations across the board. The 3M average of total nonfarm payroll gains continues to trend lower, and the unemployment rate jumped strongly to 4.3%, now 90bps off the low point of the cycle.

There is an open question as to whether the hurricane in Texas impacted the monthly job numbers, and this is possible, but what’s more important is the trend that’s been developing for the last 12-18 months.

A trend is a trend, and it should be taken seriously when sufficiently forecasted by the Leading Employment data, as it has been since late 2022.

As always, we take our collective reading on the labor market report from a basket of indicators rather than any single data point.

Nonfarm payrolls, the employment level, aggregate weekly hours, the unemployment rate, and the insured unemployment rate are aggregated into our Coincident Employment Index, which showed a monthly decline in July.

More importantly, the growth rate of the Coincident Employment Index has been “below trend” since the early part of 2023 and slipped into fractional contraction for the first time since the 2020 recession.

On a longer-term basis, there has never been a time in modern history when the Coincident Employment Index registered a sustained negative growth rate without the economy being inside a Business Cycle Recession.

A -0.1% growth rate is certainly not clear cut and could come with revisions, so we have to see more data to make a firm declaration, but again, the trends across the Leading Employment Indexes over the last 18 months, now being confirmed in the Coincident Employment Indictors is a very significant Business Cycle signal.

We frequently reference the growth rate of the EPB Coincident Employment Index and nonfarm payrolls. Nonfarm payrolls is one of the components held within the Coincident Employment Index, but traditionally, the most lagging of the metrics.

Therefore, we almost always see the Coincident Employment Index weaken and fall into contraction before nonfarm payrolls, which is happening again today.

In fact, we can look at the ratio of the Coincident Employment Index and Nonfarm Payrolls as a Business Cycle indicator.

When the ratio is declining, the Coincident Index is underperforming nonfarm payrolls and picking up underlying weakness.

The ratio peaked in May 2022 at a very elevated level and has now declined for over two years, falling below the pre-pandemic levels with no signs of slowing down.

The analysis from the Coincident Employment data remains one of clear deterioration that is highly consistent with the potential crossover from the Slowdown Phase of the Business Cycle to the Recessionary Phase.

We use several baskets of Leading Employment Indicators to help gain confidence on future trends in the labor market and to have conviction as to whether trends are actually trends or just monthly noise.

In this case, it’s clear that the trends in Coincident labor data developed after contractions in broad Leading Employment Indicators, which is a Business Cycle concern.

The EPB Leading Employment Index started to contract in late 2022, as did the Conference Board Employment Trends Index.

Importantly, neither index sustainably exited contractionary territory, which confirmed that we should be looking for labor market weakness. The signal from the Leading Employment Indicators remains the same: more labor market weakness should be in front of us with the usual monthly noise that comes within a trend.

Job losses in the economy always accumulate from what we call the “Very Cyclical Employment Basket” of residential construction, manufacturing, temporary help services, and trucking.

Very Cyclical Employment peaked in 2022 and has contracted nearly 300,000 jobs, confirming the developments we are seeing in the unemployment rate.

However, all the job losses are still coming from temporary help, and trucking as residential construction and manufacturing employment continue to increase.

Large, non-linear increases in the unemployment rate almost always come from these larger cyclical categories, so we have to keep a close eye on them.

Manufacturing has been steadily weaker than residential construction. Residential construction has not shown any sustained job losses this cycle, while manufacturing is showing on-and-off job losses.

More importantly, as we covered in Weekly Economic Briefing #30, manufacturing employment is being helped up by one single category—transportation equipment or autos.

The chart on the left shows the 3M average pace of monthly job gains for manufacturing, and the right-hand chart shows manufacturing excluding transportation equipment.

The manufacturing sector, aside from autos which is admittedly a very important category, has showed steady job losses month after month for 19 months.

So, there is more weakness within manufacturing than it appears on the surface, but overall, residential construction and manufacturing still need to show further deterioration for the traditional Business Cycle Sequence to continue to play out and that is highly likely given the trends in the Leading Indicators and the backlog issues we discussed at length in the July Business Cycle Trends Report.

In economic theory, a perfect balance is when labor demand matches labor supply.

While these estimates are only as good as the data is accurate, we can roughly estimate labor demand and labor supply.

Labor demand is the current employment level + additional job openings.

Labor supply is the labor force plus marginally attached workers.

When labor demand exceeds labor supply, there is a labor shortage and an upward squeeze on wages.

Conversely, when labor supply exceeds labor demand, there is excess labor and sustained low wage growth.

If we plot labor demand and labor supply as a ratio, we can see that levels over 1.0 are when demand exceeds supply. Labor demand was below labor supply based on these measures for decades, which partly contributed to very weak wage pressure and inflation.

In 2017, labor demand and labor supply moved into perfect balance at 1.0 and we started to hear about labor shortages in the goods economy due to skills mismatches in manufacturing, trucking and construction.

After the pandemic, there was an explosion and labor demand vastly exceeded labor supply, leading to a major labor shortage, wage increases, and inflation pressure.

Monetary policy has been working exactly as designed, bringing these metrics back into balance, and actually slightly under balance which means excessive wage pressure is gone.

In a perfect world, the Federal Reserve would like to hold the labor market exactly where it is today. Inflation has averaged roughly 2.0% over the last several months, with a slow increase in the unemployment rate and a perfect balance between labor supply and labor demand.

However, the theory goes that if you want a labor market that neither tightens nor loses, the policy rate should be set at “neutral.”

It’s an open question as to what the neutral rate is because it’s somewhat of a loose concept, but conventional wisdom is in the range of 1.5% to 3.0% to use a wide band.

In other words, if the Fed wants to freeze labor market momentum exactly where it is today, it needs to be at neutral immediately. This sudden realization is likely the reason behind the rapid repricing of interest rate expectations down to a terminal rate of around 3.0% as of this update.

If monetary policy remains above neutral, then this labor demand and labor supply balance will continue to drop, leading to more unemployment and weaker wage pressure.

My personal view is that the neutral rate of interest is not much different than the pre-pandemic regime, towards the lower end of that 1.5% to 3.0% range.

Overall, the pace of nonfarm payroll gains continues to cool, and the increase in the unemployment rate is accelerating.

The Coincident Employment Index slipped into fractional contraction for the first time this cycle, an extremely important signal as it was foreshadowed by sustained contractions in Leading Employment Indicators for several months.

Labor demand has slipped below labor supply, which will bring dramatically lower wage pressure.

If the Federal Reserve wants to freeze labor market trends exactly where they stand today, the policy rate should be set at “neutral.”

If you found this report informative, please share it with anyone you think would find it valuable. It is a great help to us to have our work shared with a broader audience.

Interested in receiving more Business Cycle reports just like this?

Consider our Weekly & Monthly subscriber publications.

Our goal is to help you stay informed and ahead of major Business Cycle trends with just a few minutes per month through our animated video presentations.

If you are an institution, corporate management team, or operator of a cyclical business and need help navigating the current Business Cycle environment, please book a call with us so we can learn more about your business and explain how we can best help improve your operation.

Did you know that all our reports are published as an animated video?

Here are the first 2-minutes of this Weekly Economic Briefing in Video Form.